In this article, I want to discuss the kinds of properties that make working with CSS hard and the kinds of properties developers want out of the system. We will then analyze common solutions and how they stack against these goals. Finally, I will propose a solution that checks off all the boxes.

Like so many other things on the web, CSS was designed for documents, not applications. As such, the development community has been fighting with how we can use CSS to style our apps and components in a scalable and enjoyable way with limited success.

The web was designed for documents, and because of that, there was a lot of talk about the semantic web. The idea was that you describe the document in HTML with meaningful tags such as <article>, <aside>, <details>, <figure>, <footer>, <header>, <main>, <nav>, <section>, and <summary> to name a few. And while this describes the content of the document well, it does not specify how it should be rendered visually. For that, we invented stylesheets. The idea is that each semantic document could have many different stylesheets to present the same data in different formats.

So what was needed was to style the semantic markup in a way that would be completely external to the HTML. Enter stylesheets and CSS selectors.

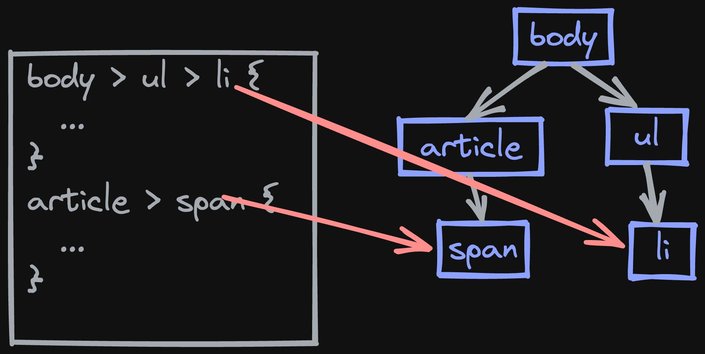

CSS selectors allow the stylesheet to refer to the elements in HTML. The problem is that the CSS selectors are complicated. It is very difficult to reason when each selector will select and in which order. For the browser to know how to style an element, the browser needs to have full knowledge of all the styles and execute each selector to determine which selectors apply and what the final combined style should be. Selectors are powerful (allowing us to style any HTML document) and complicated to reason about. We are never sure what kind of visual change a given stylesheet change will have.

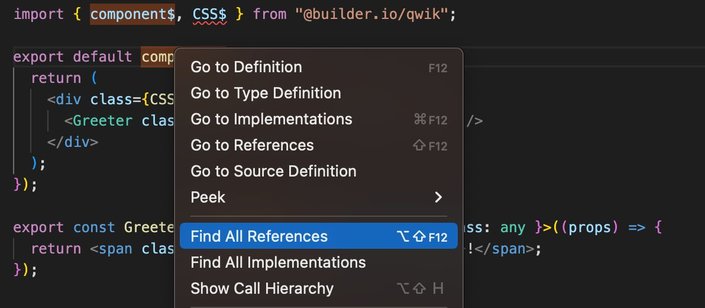

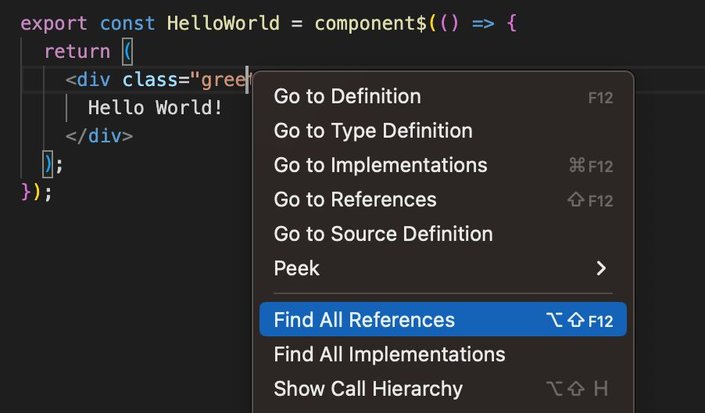

As developers, we love our tooling to help us navigate and wrangle our code. One of the best features of an IDE is to find all references. Finding references is used to help us refactor our code by renaming our variables.

Query selectors are not conducive to finding references because they can only be evaluated in the context of a complete HTML document. (Sure, some queries are specific enough that we don't need the whole document, but you can never be sure.) And therein lies the problem. We don't have good tooling to work with our styles. Lack of tooling means that invariably the stylesheets end up as append-only documents as everyone is afraid to remove anything from them for fear of unintentionally breaking something.

We are not building documents! We are building applications. And we are abusing stylesheets to get what we want out of them. As developers, we want the following list from our styling system.

We want to be able to easily find all of the styles which refer to a given element. Because styles compose and because they have selectors, finding all of the possible styles which refer to an element can only be done at runtime when all of the styles are present. Yet our tooling works at compile time. We are too used to just alt-clicking on symbols and expecting to be taken to the definition. With stylesheets, that is not possible.

One of the hardest problems in computer science is naming. Because of that, refactoring tools which allow us to rename our symbols are invaluable to us. Renaming styles is hard because it is hard to know all the locations which the style could affect and how the styles compose. See find-references above. This means, in practice, that the developers don't refactor their styles because there is a good chance that such an operation would break the visual representation of the application. And BTW, visual tests are some of the hardest tests to write.

We often write more styles than the application actually needs. So we want the not-needed styles to be automatically removed and not shipped to the browser. Dead styles are just dead weight and they should be removed. But once again, we need to find all references of styles to have reasonable tree-shaking solutions for styles.

Styling often requires naming things. Names could have collisions, which would result in styles affecting each other. This makes composing libraries and components hard. So as developers, we look for good scoping solutions. Allowing two different components to use the same name without worrying that their styles will collide is a requirement.

Because we are forced to name things, we want a type system to verify that a class name in the stylesheet and the class in the DOM match and that there are no typos. But yet again, find-reference proves it is hard to write a type checker which can verify all of this.

We want our styles to compose easily. Have a parent component add to your styles or override the themes variables.

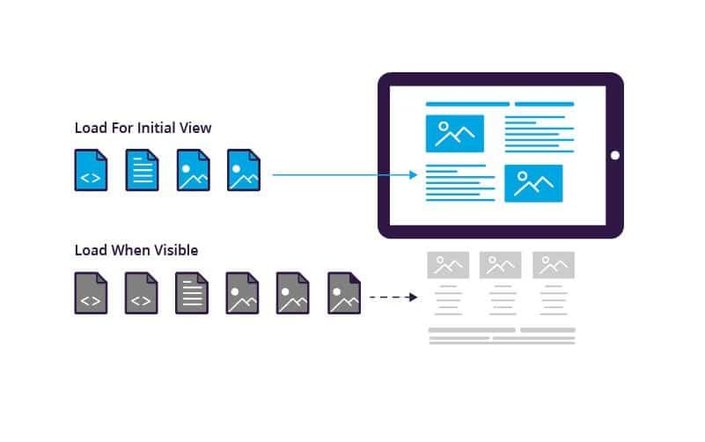

Finally, we want a lazy loading solution so that the styles can be loaded only as needed so that our application startup performance is not overwhelmed by too much CSS.

Find references / rename / tree shaking / type safety / lazy-loading; it is all different facets of the same coin. If you can't find references, you can't rename, tree shake, lazy-load, or have type safety. Solving static analysis of styles is paramount to enable all other benefits.

CSS selectors are powerful because they need to specifically select elements deep in the render tree. But their power means that they are extremely hard to reason about statically. Full knowledge of all selectors and a full DOM tree is required to know if a selector applies.

When developing applications, we must be able to reason about our code in a static matter. Selectors are ill-suited for this. Instead, when building applications, we need to constrain the selectors to a subset that can be statically analyzed.

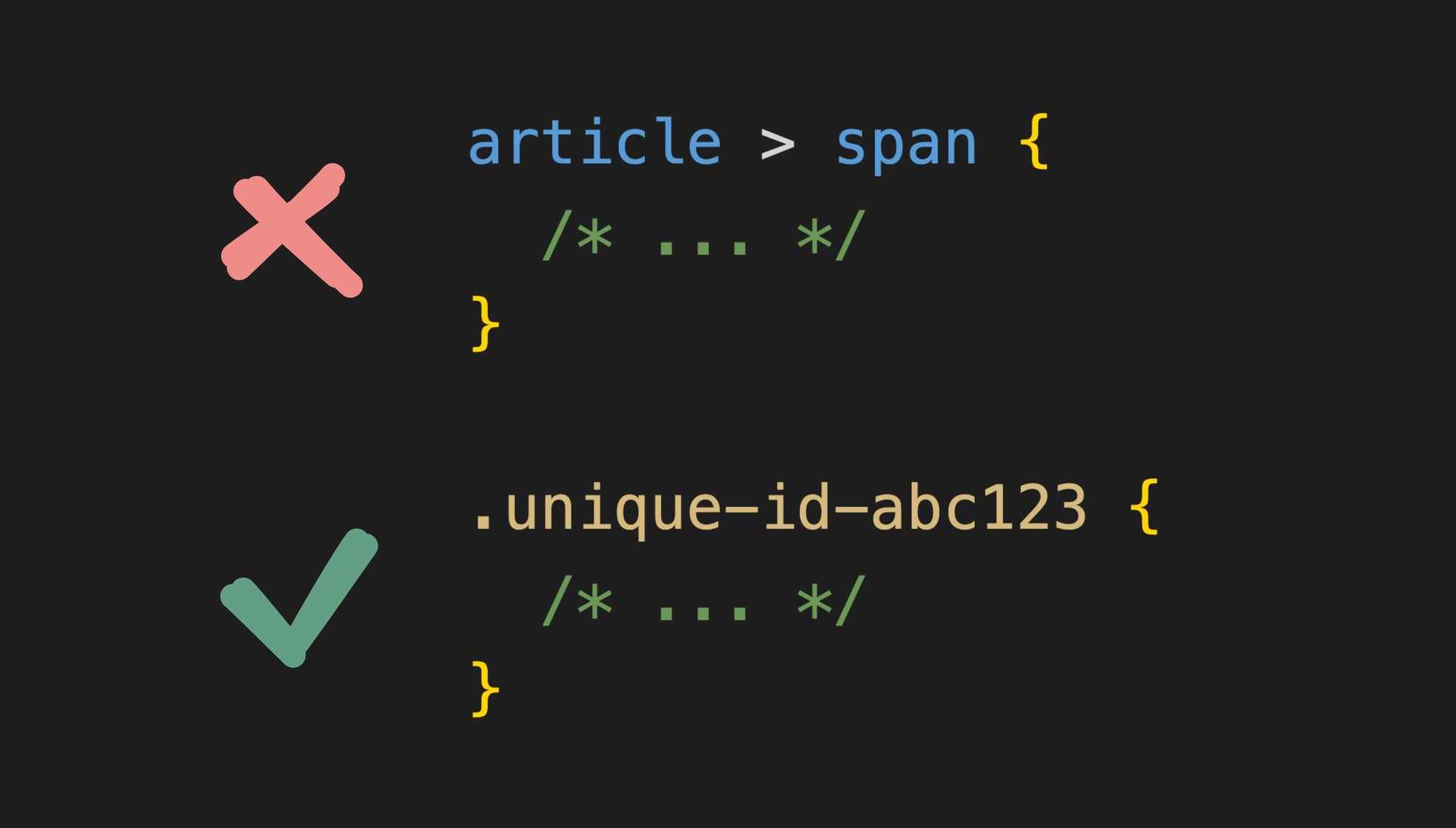

Applications must limit themselves to class selectors only .class-name {} without additional parent constraints or composition. By restricting ourselves to such a limited usage, we can reason about our codebase statically. Call it the CSS the good parts.

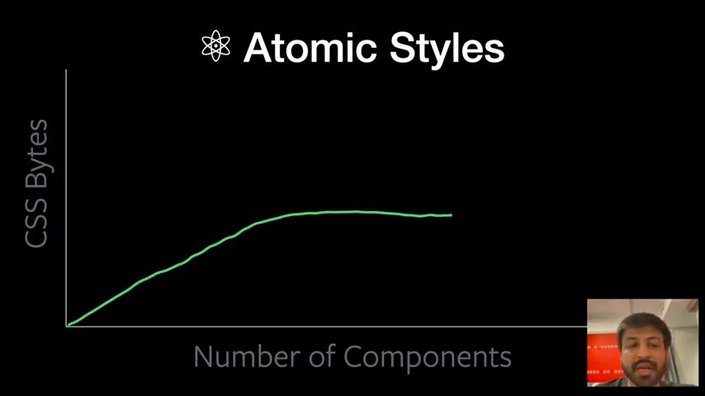

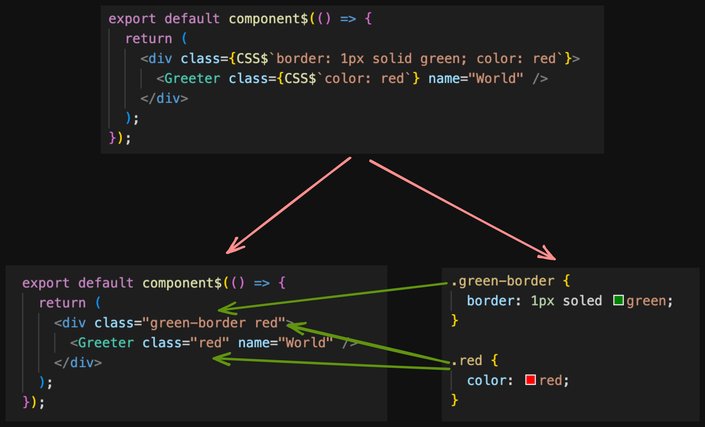

Our selectors often apply multiple styles. This makes them very specific and hard to reuse. What if each selector applied a minimal set of styles instead? (See StyleX) the argument here is that over time the number of styles reaches a limit even as the application grows.

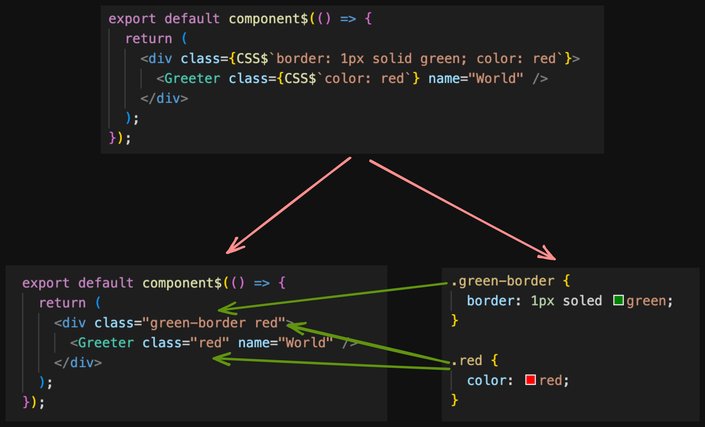

Take the code below as an example. The developer can express the styling directly inline without concern about style collision or re-use. The atomic nature of the CSS transformation is that each of the styles gets broken down into its atomic unit and saved into the stylesheet. The tooling there generates a unique name (not collisions) and automatically reuses the atomic style in other locations.

The value added to this approach is that the developer does not have to consider style reuse or worry about style collisions. The tooling just does the right thing.

A canonical way to build a page is to create an HTML and stylesheet file. The problem is that it is not the way our brains work. When we create an <element> we immediately think about styling it. And so, we want to insert style as we create it without getting distracted.

You see, non-inline-able style requires the developer to make mentally draining choices.

- I need to choose a name for the class

<div class="some-name">. - Where do I put the

.some-nameselector? So now I need to create a filemy-component.css. - Where should I put the new CSS file? Should it be next to the component or in a special style directory?

- How do I ensure the style file is loaded at the right time?

At this point, so many decisions and pushing work onto your mental stack had to be made that you forgot where you were or why you were writing that <div> in the first place.

So let's go through some of our common solutions that try to address this problem.

Let's do everything in CSS. When do we load? Just load all of it upfront? Which selectors are being used? Hard to tell, so the CSS file becomes append-only, as everyone is afraid of touching anything. Pure CSS is fine for small applications but goes out of control for large ones. It does not scale and it is hard to compose because a new change runs the risk of having unintended consequences, as selectors are hard to reason about.

Vanilla CSS has failed us as a solution, which is why people have been inventing CSS frameworks.

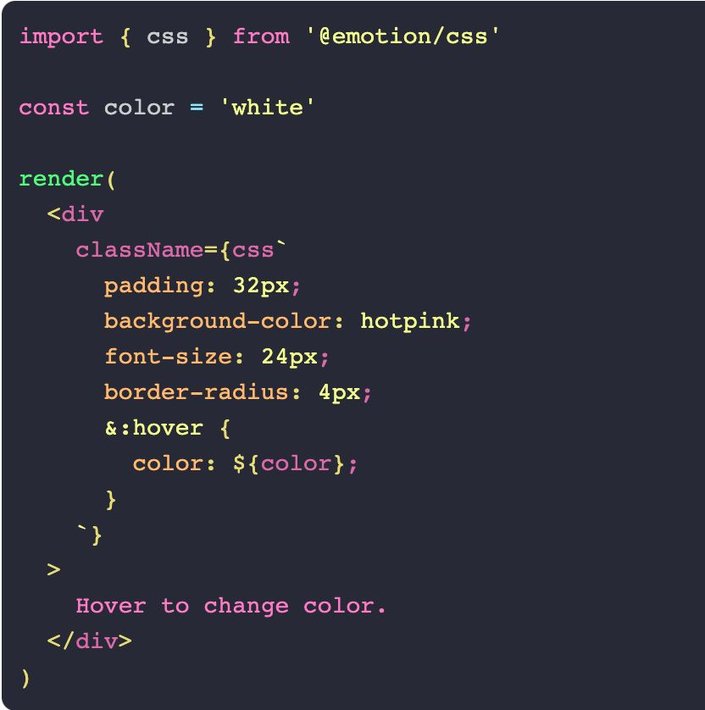

CSS-in-JS is very popular because the styles can be inlined into the markup. This means the developer does not have to spend the mental energy to create a name for the class. It also means that it is very clear which CSS affects which element. The styling is now type-safe and it only loads when the component loads.

So much win; what can be the downside? Well, CSS-in-JS is fully runtime dynamic and, therefore, can’t be analyzed statically by our tooling. The CSS-in-JS implementation is too powerful for our tools to reason about it. So lazy-loading or tree-shaking is not an option.

The non-static nature of CSS-in-JS is especially problematic with SSR. (See Why We're Breaking Up with CSS-in-JS) A stylesheet can't be created until the component executes so the styles can be created. But this means that either the HTML has to be buffered or the style is inserted after the component, which can cause a flash of unstyled content.

The dynamic nature of the CSS-in-JS also means that it is not possible to separate the style information into a stylesheet and loaded separately from the component. For example, if SSR renders a component, the second instance of the component does not need the CSS-in-JS because the first SSR instance of the component already has it loaded. So loading it again as part of the component is wasteful.

Finally, emotion.js CSS-in-JS implementation is not atomic. There is no upper limit to the number of styles you need at runtime. This may lead to performance bottlenecks as the number of styles grows without an upper bound.

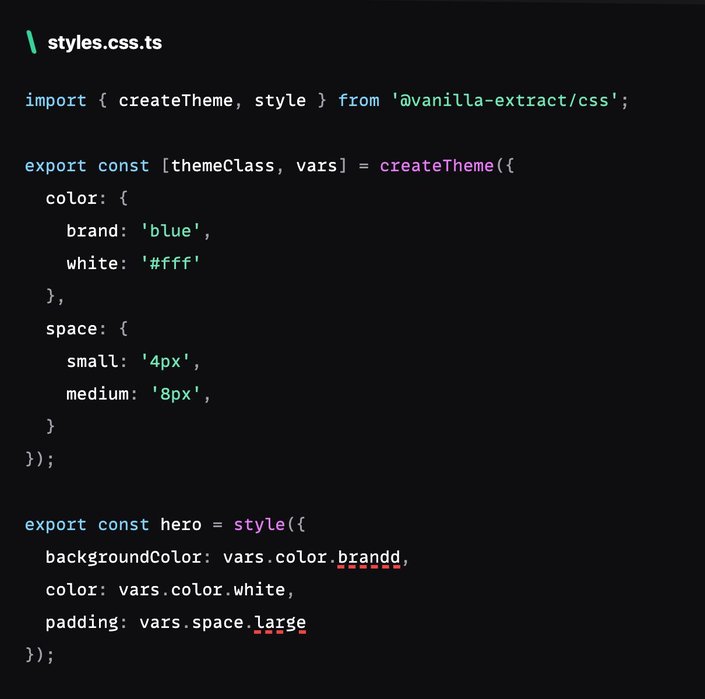

An alternative to CSS-in-JS is Vanilla Extract, which combines static analysis but feels like CSS-in-JS.

Vanilla extract has many nice properties but it does have a cost of forcing the developer to put all of the styling information into a separate file named foo.css.ts so that the Vanilla extract compiler can statically extract the styles and generate a stylesheet.css. The only downside of Vanilla extract is that it can’t be inlined into the component code, and it is not atomic, meaning that there is no upper bound on the amount of CSS it can generate.

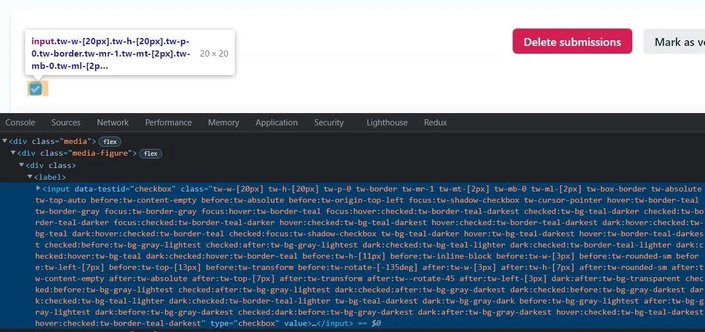

Tailwind is another popular solution that is atomic. Instead of coming up with class names, the names are already created for you. This frees up the mental effort required for creating names by the developer and therefore prevents breaking the mental flow when developing components. Because classes are atomic, the styling is automatically stopped for your component. There is a finite set of classes that tailwind provides, and no matter how large your application grows, it will never grow past that set.

In contrast to CSS-in-JS, the tailwind is fully static. It is possible to run the compiler at build time and extract all the necessary class names ahead of time and convert them into a stylesheet, which is exactly how tailwind works. This makes SSR easy.

The downside is that we have created yet another language for expressing styles. You can't just write margin: 4px instead; it is m-1. The end result is that the class attribute is often abused as multiple lines of classes need to be added.

Regardless of where you sit on the tailwind debate, Tailwind proves that static (ahead-of-time classes) and atomic classes are scalable. They can be used to build large applications. I think the debate is not about whether you can use tailwind but rather about the syntax that the tailwind presents. Can we have the static power of tailwind without the class hell tailwind sometimes leads down to?

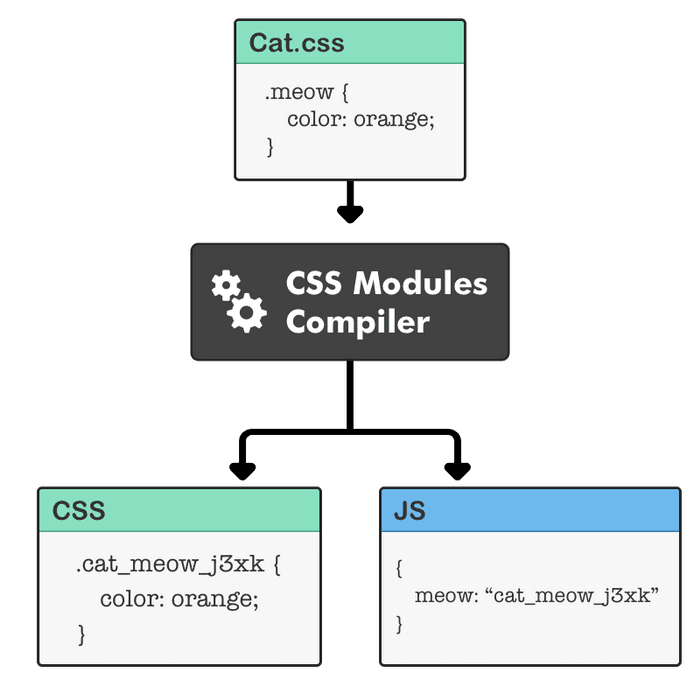

CSS modules allow you to write a CSS file with class selectors. When the CSS module gets imported into your application, the selectors get renamed into unique selectors, giving you a scoping of styles. The CSS module import also gives you a mapping object to refer to styling human-readable names, but the mapping returns a mangled name that is scoped.

CSS modules have many of the properties we want. They are scoped, typed-checked, and rename-able, but not inline-able and not atomic.

I will postulate that what we really need to build applications is a system that has these properties:

- Statically analyzable: We need a system that is statically analyzable. We need this to do find-by-reference, renaming, tree-shaking, etc... We need tooling to help us along. In practice, this means that we need to rely on very specific selectors with guarantees to have only one match. A system-generated class names that are unique and provide scoping and reusability.

- Atomic: We need the selectors to be atomic. But as a developer, we don't want to think about styling in the form of atomic parts; instead, we want to think in terms of the result we want, and the system should find and extract commonalities for us.

- No new syntax: We don't want yet another syntax. CSS properties are the syntax we want. Nothing new to learn.

- inline-able: We want to be able to style the component as we are creating the component. There should not be a need to change files, and thus think about how to refer to things, which necessitates that things have names.

CSS styles are the way to style our content. Stylesheets were designed for styling content, not applications. The primary problem is that the CSS selectors can't be reasoned about without knowing all stylesheets and HTML. To better support applications, developers have tried several approaches. The primary use case to solve for is the ability to inline styles. CSS-in-JS is too dynamic, which makes SSR and lazy loading difficult. Tailwind is static, so it works great for SSR but makes a mess of class names. Vanilla extract seems to be a good compromise between static analysis and generating good class names. Still, it can’t be inlined in the existing JSX files (requires separate files for compiler extraction.) What is needed is something like CSS-in-JS but more static to get SSR's benefits.

Introducing Visual Copilot: convert Figma designs to high quality code in a single click.